DECEMBER 2011

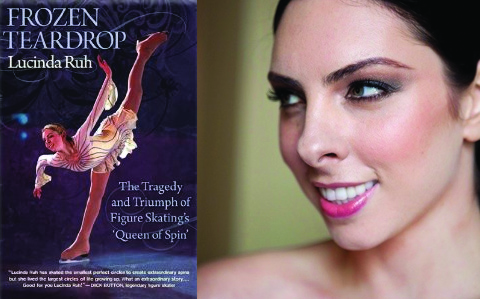

An interview with Lucinda Ruh. Ms. Ruh is a 2-time Swiss National Champion, star of both Stars On Ice and Champions On Ice, and was twice named one of the “25 most influential people in figure skating” by International Figure Skating Magazine. She astounded crowds worldwide with her gifts in spinning as an amateur skater throughout the 1990s, competing in eight World Championships and on the Junior and Senior Grand Prix Circuits. Her spins influenced how spins were judged when IJS was adopted, and in 2003 she became the World Guinness record holder for the longest spin on ice. Her own website is www.lucindaruh.com, and she is the author of “Frozen Teardrop: The Tragedy and Triumph of Figure Skating’s Queen of Spin.” We talk about her fascinating life story, how she was never interested in an Olympic Gold medal, and how she came to wear that iconic gold jumpsuit. 1 hour, 5 minutes, 23 seconds.

Win a copy of Lucinda Ruh’s Book!

Two lucky winners can win a copy of Lucinda Ruh’s book, “Frozen Teardrop: The Tragedy and Triumph of Figure Skating’s Queen of Spin.” It’s a fascinating look inside Lucinda’s experiences growing up in the sport, and is at once both devastating and uplifting. (Read my review of “Frozen Teardrop” here)

To enter, send me either through email, twitter or my Facebook page the answer to the following question about Lucinda Ruh: she mentions during the podcast (about 32 minutes in) that there is one spin she does that she wishes were named after her and known as the “Lucinda” spin. Instead it is commonly referred to as . . . what?

All entries received between December 23, 2011 and January 30, 2012 are eligible. The winners will be picked at random from all correct entries sent. Click here to learn more about how to enter.

Read my review of Lucinda Ruh’s “Frozen Teardrop”

Thanks to Fiona McQuarrie for transcribing these interview highlights:

On her most embarrassing skating moment: I was quite young, maybe 11, 12 years old, and I was living in Japan, so I had to keep on going back to Switzerland to do their tests. Because even if I wasn’t doing the Japanese tests they weren’t counting them for Switzerland, to compete for Switzerland. So I always had to go back, and I would always do a couple of tests in a row because it was quite a long trip. So I was about 11, and everyone was like, oh my gosh, this girl is coming from Japan, and no one really knew me yet, but, you know, my name was buzzing in their ears so they were all expecting this incredible girl [laughs]. And the first thing I do is go on the ice with my guards, and fall, like, flat on my face. So that was the very first thing they saw of me. But afterwards I did really great and passed all the tests. So probably that moment was quite embarrassing. All the way from Japan to go on the ice with my guards [laughs].

On training in Japan with coach Nabuo Sato, and not getting a lesson with him for the first six months: In Japan, respect and loyalty and discipline are so important that, in a way, I think [working on her own] taught me great lessons, even though I was only about seven or eight years old. In one way, it’s kind of painful to think, gosh, I really had to do that, all your friends are having lessons and you’re kind of like training by yourself. And I really had to go every day — otherwise he would think, well, this child is really not motivated in skating, and not disciplined. And that’s when my mother really became my constant, you know, because I had nobody else. I was eight years old so I really leaned on my mother at that time, and she was helping me with my skating. Not really my coach, but as a mother and guiding me a little bit. That’s when we became really really strong together.

This was also what was kind of hurtful but also helpful to me, as a person, not always as a skater. I was an outsider. We were in Japan, we were the only foreigners. I think my mother and father felt like, if we’re not going to follow their rules we’re not going to be accepted into their society. So that’s very strong….but we were always in a foreign country, always the outsider, always the only one out. So they probably felt like, if we don’t do that, no one’s going to take our child. And that’s how I kind of started feeling about myself, too, that I always had to conform to someone else’s beliefs or to someone else’s culture, and I could never really be me.

On how her success while training in Japan led to her being bullied and more isolated: As a child, it’s not easy to deal with, because you’re trying to do the best at whatever you’re doing. And I had a very strict coach, and then I still have Swiss-German parents, who are very tough, very disciplined, and hard work comes first, there’s no excuse…and so, as a child, I thought, I have to work hard, I have to get better. And then the more I got better, the more I was isolated. In that part, you become very alone. And I think skating in general is quite a lonely sport, especially singles. Pairs, maybe you have that bit more of camaraderie with your partner. But as a singles skater, sometimes — at least, I did, I felt everyone was against me, except my mother, maybe.

On her training regime in Japan: My father came home from a trip and said I have to spin better than the Swiss spinners — at that time there was Denise Biellmann and Nathalie Krieg. And he said the only way I would leave my name in history was to do something that no one else has done, and he wanted that for me. And he was quite stern about saying that to me, and I was only about seven and that really stuck with me. So that was kind of my goal. And so that was like a snowball getting bigger, and that was our goal, so we worked and worked and we just had to get there, without question. And we never questioned anything, and we worked like crazy. I mean, I woke up and I’d have to run in front of the car, my mom would drive behind me, for about ten minutes, and then I’d jump in the car and eat some breakfast, and then she’d drop me off again, before the rink, and I’d have to run to the rink and warm up, and skate, skate, skate, and I went to school full-time, I didn’t home-school…so I went to school, and then went to the rink and skated until about 10:30 at night, and then ran home. It was non-stop, and Saturdays was non-stop and Sundays was non-stop. And going on something like a sleepover, that was unheard of. But you see, I didn’t know it either, so I didn’t really miss it growing up. I was at school but I was so far removed from their life outside of school that I didn’t know it really existed. I was in my own little world.

On seeing Japanese coaches beating their students, and then being beaten by her own mother: If you didn’t work hard enough, or didn’t do something good enough, you had the consequences. And then the parents would take over off the ice. It was something of a normal occurrence. One was really terrible. I remember going to the rink in the mornings and the evenings, and there was this little café right next to the rink. And so there was a big rink and this smaller rink where we used to do compulsories, and right next to it was this long café. And [the coaches] used to bring this boy, he was about 12, 13, into this café, and the mother would watch, and they’d beat him for the longest time while we were training. And they’d beat him and beat him and he’d be screaming, and we’d try to play the music a little louder so we wouldn’t hear him. And he was shaking. This boy could barely walk straight, he was so shaking every day. And the memory of that, I could barely skate while this was going on because it made me so sick to my stomach. But no one did anything. You know, it happened, and the next day it happened again…

My coach never hit me, he never touched me, so I think my mom thought it was her turn to take over. That’s the way everyone was doing it. I think she watched and she took over. Nobody knew [that she did this] — in public, she would not. And [when writing the book] I wanted to be sure that, you know, so many people say they are hurt by it and upset by it, and of course I am. I feel like, especially when it’s your own mother doing it to you, of course there’s a lot of pain there. But there was so much frustration behind there that caused her to do that, that I can understand, almost. I’ll take the beating for her frustration. Because my dad was travelling about 95% of the time, and again, we’re in a foreign country, foreign language. It’s not like we’re going from Germany to Paris or America to Canada – from Switzerland to Asia, it’s a big difference, culturally, language-wise. And to be a mother with just one child, it’s very hard, and I think my father was not able to be there to support her in that way, emotionally. And with the frustration of skating and maybe getting only 20 minutes a day for a lesson, I think the competitiveness took over, and I think watching what the other parents were doing, and the teacher did not touch me, I think maybe that put pressure on my mother to make me perform better…as a child, I didn’t understand quite why she was doing it to me, because I thought I was working so hard, it wasn’t like I was lazy or wasn’t trying. So that part hurt me more, not understanding why she could get so mad at me. That was more hurtful than the actual hitting. But I don’t know, it happened and you can’t do anything about that, so all you can do is look back and try to understand it and try to move on.

On why Swiss skaters are known for spinning: [I had] no Swiss coach, no Swiss water, maybe Swiss chocolate during Christmas time [laughs]. Unless it’s really in the Swiss genes, something about spinning, I don’t know, maybe it has to do with what the watches do, the spin, I don’t know [laughs]. But I really self-taught it. My coach in Japan, he emphasized very much on the back scratch spin from a very young age. He didn’t really tell me how to do it, but he emphasized that it become really good. And that became the basis for a lot of the spins.

On the innovative spins she created: I invented so many different spins, especially if you count all the different arm movements I had. I started with the side layback, and the pancakes, and the twisting sits, and they were all from me. But the one that’s so popular right now, the pancake one, I would really love it if they called it the Lucinda spin [laughs].

On changing coaches throughout her career, usually without a tryout with the new coach first: That’s also why I wanted to write the book, because as a first-time mother or parent in the skating world, there’s so many things that you don’t know and there’s so many things that are not exposed. So I felt like I also had the chance to help first-time parents. We just did not know [to have a tryout first]. But then again, I don’t regret anything.

On being sick or in pain from injuries for seven years: Nobody told me to stop. The spinning — gosh, I don’t know, at that time I was the only one in the world doing those spins, and I was like, I’m the only one so I have to do it for everybody. No matter what you’re feeling, it’s not the spin’s problem. That’s what we thought. I’m not being arrogant in saying this, but they were beautiful, and people were saying, they’re so beautiful, there’s no way you’re going to stop, that’s your livelihood. So no matter what, you’re going to spin.

In one way, that was kind of exhilarating to find out [that the ongoing injuries were caused by concussions from the force of spins] but it was also very painful because it meant that I couldn’t spin any more. So it was almost like the thing I loved the most, the thing I did best, was taken away from me. I did not quite understand why something that made me so happy and was making other people happy was causing me so much pain. That was incredibly hard, to have that taken away, not me deciding I didn’t want to spin any more. It was not a choice.

Now I still bump into things, I still drop things because I lost a lot of equilibrium in my ears and my eyesight. And I just feel kind of out of balance for most of the day. But I’m much much better. I was basically bedridden for two, three years where I couldn’t basically walk upstairs. But now I can go about daily life so it’s better. But it will probably take more years, given how many years I inflicted on myself.

On what she tells the students she coaches: I’m fortunate in that the kids that I have, they’re very competitive but they’re…let me see, how can I say this? I really try to instill in them that it’s not just landing a double axel that’s the most important thing in life, it’s really becoming a champion in life. And to me, becoming a champion in life is achieving their dreams, whatever they may be, but without losing yourself and your self-worth and your self-respect. Because at the end if you’ve lost all of that, what did you win for? Because that’s kind of what I went through. I lost everything and I still had my spins, and in the end I didn’t even know who I was without the spins. So I really try to instill in them the whole character of a champion in life and on the ice, while achieving their dreams. And I also explain to them that the most important relationship they will have is the one with themselves. Once they truly understand themselves and respect themselves, then they can really have a relationship with anything else, with skating, with their parents, with anybody or anything that they really want to achieve.

On how she feels now about her accomplishments in skating: I can’t do what I used to be able to do, but now I can actually watch my videos and enjoy and appreciate what I did. My biggest regret is that I never enjoyed it as much as I think I should have. I think humble pride is always good to have within yourself, of what you’ve accomplished and what you’re doing. Without that, it’s hard to keep on going and be successful. Not an arrogant pride, but at least to acknowledge to yourself what you have done, and I don’t think I ever did that. Now I can look back at the videos and think, maybe I did something a little good [laughs].

Ruh wishes the “pancake spin”, which she originated, were call the “Lucinda Spin”.

TK